cross-examining elizabeth

Speech, Silence, and the Central Park Five at Columbia University

Charles Wenzelberg

Charles Wenzelberg

MAY 5, 2019| ![]() THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR [unpublished]

THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR [unpublished]

What happened to Patricia Ellen Meili in Central Park on the night of Wednesday, April 19th was awful. However, it was anything but an anomaly in 1989 New York City. This was a New York with crack on the streets, graffiti on the subways, and crime all over. An average of 36 murders per week caused street smart people to use at least two and even up to four locks on their doors plus a police lock for added protection. Just in the week of Meili’s brutal beating and rape alone, there were 28 other reported incidences of first-degree rape or attempted rape across the city.

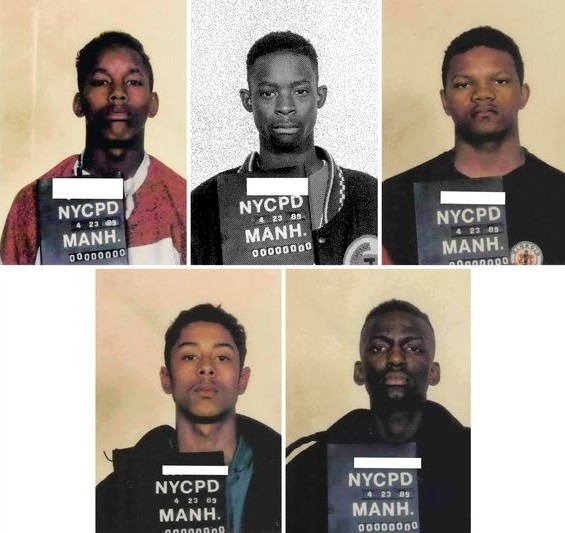

From our present-day perspective, it is easy to forget that when Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, and Raymond Santana Jr. – the East Harlem teenagers who, along with Korey Wise, would later become known across the city as the Central Park Five – left the Schomburg Plaza with 33 to 39 other Black and Latino youth at around 9pm, the Central Park that they traversed was not the “oasis from the insanity [of the city]” advertised in today’s Lonely Planet. The buildings were crumbling, the garbage was overflowing, and the green areas had all turned brown, even in April’s spring.

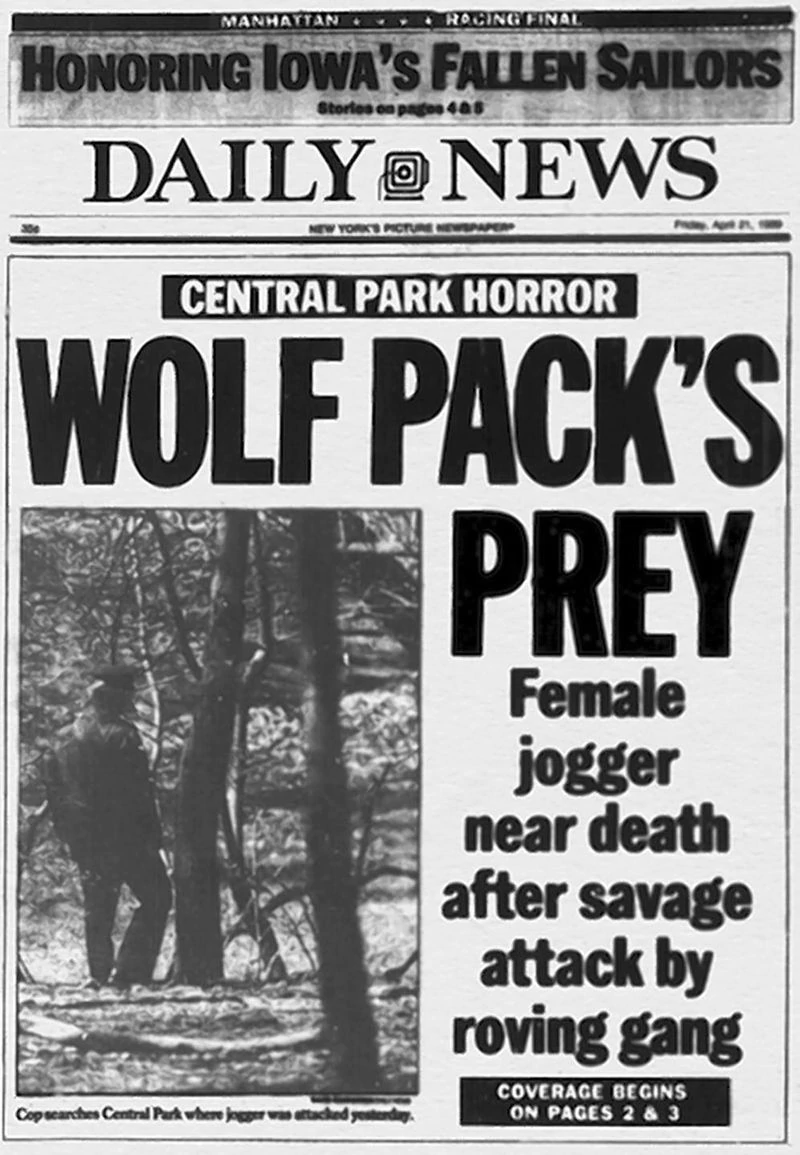

In a New York where the jails were overcrowded and in a park whose grassy fields had dwindled down to dirt and dust, there was, in spite of the overblown media attention, nothing truly exceptional about the case. In fact compared to other crimes, the Central Park Jogger saga had ended quite well. Meili, the tragic victim who had been beaten beyond recognition, regained her health, and “the wolf pack,” as the media referred to McCray, Richardson, Salaam, Santana, and Wise who were accused of attacking Meili, was locked away with sentences ranging from seven to 13 years thanks to the hard work and diligence of the legal team led in part by the curly-headed assistant district attorney, Elizabeth Lederer, 36 years old at the time.

Michael Norcia

Michael Norcia

However, 13 years later, the perfectly woven tale of a successful, young, White woman nearly slain by the lust and violence of dark thugs on a dangerous night in a crime-ridden city began to unravel as a new confession to the crime appended an afterward to the happy ending of the Central Park Jogger case. On December 19th, 2002, New York State Supreme Court Justice Charles J. Tejada vacated the convictions of the Central Park Five, each of whom had already served their full sentences, based on a reinvestigation of the case that determined the falsity of the Central Park Five’s confessions and proof that serial rapist and murderer Matias Reyes was, in fact, solely responsible for the crime.

With Reyes’ confession and his DNA confirmed to have been on Meili’s body, a shadow spread over the Central Park Jogger drama, casting its characters in a new light. The villains became victims. It was no longer the Central Park Jogger case. It was the Central Park Five case as the wrongfully convicted youths were held as tragic heroes, much as Meili had been perceived a decade earlier. The then heroes became villains as Lederer, once praised for her performance in a landmark case, became, in the eyes of many, the embodiment of a racist rule of law as she was accused of coercing false confessions and ignoring the gaping inconsistencies in the stories that had been crafted about the crime.

It was the Central Park Five’s speech, their taped confessions, that were used as the primary source of evidence against them, and it was Reyes’ speech, his eventual admission of guilt, that led to the Central Park Five’s exoneration.

Much of the aftermath of this case though has been marked by silences. Even in the very beginning, the city’s relative silence about other incidences of rape amplified the noise around the Central Park Jogger case, a media uproar that many have identified as a significant factor leading to the public’s conviction of the five boys far before their legal trial.

In particular, silence has played a unique and significant role in the story of Lederer’s life since the Central Park Jogger case. Whereas Linda Fairstein, the city prosecutor who assigned Lederer to the case, stepped down from her position as the head of the sex crimes unit of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office after the convictions were overturned, Lederer remains an active prosecutor. Whereas in November last year, Mystery Writers of America, a literary group, withdrew the “Grand Master” award for literary achievement, which it had given to Fairstein only two days prior, because of her role in the Central Park Jogger case, Lederer has not received any comparable repercussions.

This unequal treatment could perhaps be due in part to the differences in Lederer and Fairstein’s own relationships with silence about the case. Whereas Fairstein, even after 2002, continues to defend the original investigation and assert the guilt of McCray, Salaam, Santana, Richardson, and Wise, Lederer has kept quiet about what happened.

Today, the silences around the Central Park Five, and around Lederer more specifically, are not only aural but are visual as well.

Thomas Guercio

Thomas Guercio

Nearly every publicly available photograph of Lederer taken in 1989 is in black and white. In almost all of the pictures, she wears a dark blazer, white blouse, pencil skirt, stud earrings, and white shoes. In one photograph, she is seen smiling with an expanding file folder and papers held against the crook of her right arm as she heads to court to cross-examine Salaam. One would hardly recognize her as the same smiling woman reclining on a yellow towel in a beach chair wearing a dark swimsuit and holding a cocktail in her right hand: the current cover photo of her Facebook page.

One would be even less likely to recognize her from her faculty bio on the Columbia Law School website, the first webpage that pops up when the words “elizabeth lederer” are entered into Google. When seen through the lens of the Law School, Lederer is a faceless person, a name with a vague description. Not even her Columbia email is listed.

The previously-stated el216@columbia.edu changed to ejlederer@aol.com in 2013. In spite of the original convictions having been overturned and the case’s prosecution having been condemned over a decade earlier, it was also not until 2013 that the Law School silenced any mention of Lederer’s connection to what was previously included as the first of two “high profile cases” that Lederer worked on.

This information appears to have been removed in response to an act of speaking out against Lederer’s position as an adjunct faculty member at the Law School. She has held the position at least since 2010 – eight years after the Central Park Five were judged innocent. This speech against her working at Columbia came in the form of a petition started by a man named Frank Chi, who in 2013 began advocating for Lederer’s removal from Columbia’s faculty after watching the 2012 Ken Burns documentary The Central Park Five, which renewed popular interest in the case.

The petition, simply titled “Columbia Law School: Fire Elizabeth Lederer”, has itself now been silenced. Since at least late January of this year, the link to the petition, hosted on CREDO Mobilize, has been inactive even though as late as November of last year new voices continued to speak out through signatures added to the petition.

The absence of the Central Park Five case from Lederer’s Columbia biography, a couple of her students say, is reflective of its absence from her Columbia class: sample trial practice.

“It hasn’t come up at all,” one of Lederer’s current students tells me. “Nobody’s asked about it. She hasn’t brought it up on her own… for all I know, it hasn’t been talked about.”

Facebook

Facebook

In spite of the tacit silence, another of Lederer’s current students claims that all 14 people enrolled in her class are well aware of their teacher’s past. In fact, the student tells me that, when deciding which of the three spring trial practice sections to take, they were cautioned by their advisor “that Professor Lederer is very good but that she also is a controversial figure.”

It is the controversy of a person who, as one of her students describes her, “seems like somebody who really just wants to put people in cages”, that caused 8,635 petitioners, including many Columbia affiliates, to advocate against Lederer working in our school, and yet, she remains, returning to the Law School’s Room 107 every Wednesday night to teach.

The significance Lederer’s presence as a living artifact of this history holds for Columbia and its surrounding neighborhood, the same Harlem community that raised those five young boys before they completed their childhoods in prison cells, is one story of the Central Park Five that has not yet been told. However, it is this Central Park Five story that is, perhaps, most relevant to us as students, staff, faculty, administrators, or simply curious observers of the school that has hired the person at the contentious center of the Central Park Five case.

Professor Lederer is infamous for allegedly forcing false speech and mobilizing it as a weapon against five innocent children. In exploring the ramifications of the silences surrounding her story, we can clearly see the role that University affiliates and non-affiliates have had in sustaining the symbolic power of Lederer’s legacy.

• • •

To most people in Harlem, the name Elizabeth Lederer means nothing, Michael Henry Adams, a well-known Harlem activist and historian, tells me.

“Many Harlem people, just on principle, they looked at the prosecutors and the whole police force just as pigs,” Adams explains. “And they wouldn’t see [Lederer] as any different or more benign than any of the rest of them.”

Adams references a long and well-documented history of racially-biased interactions with representatives of government and law enforcement in Harlem. The relationship between Harlemites and law enforcement has been one of distrust and abuse, qualities not all that different from Columbia’s own relationship with Harlem.

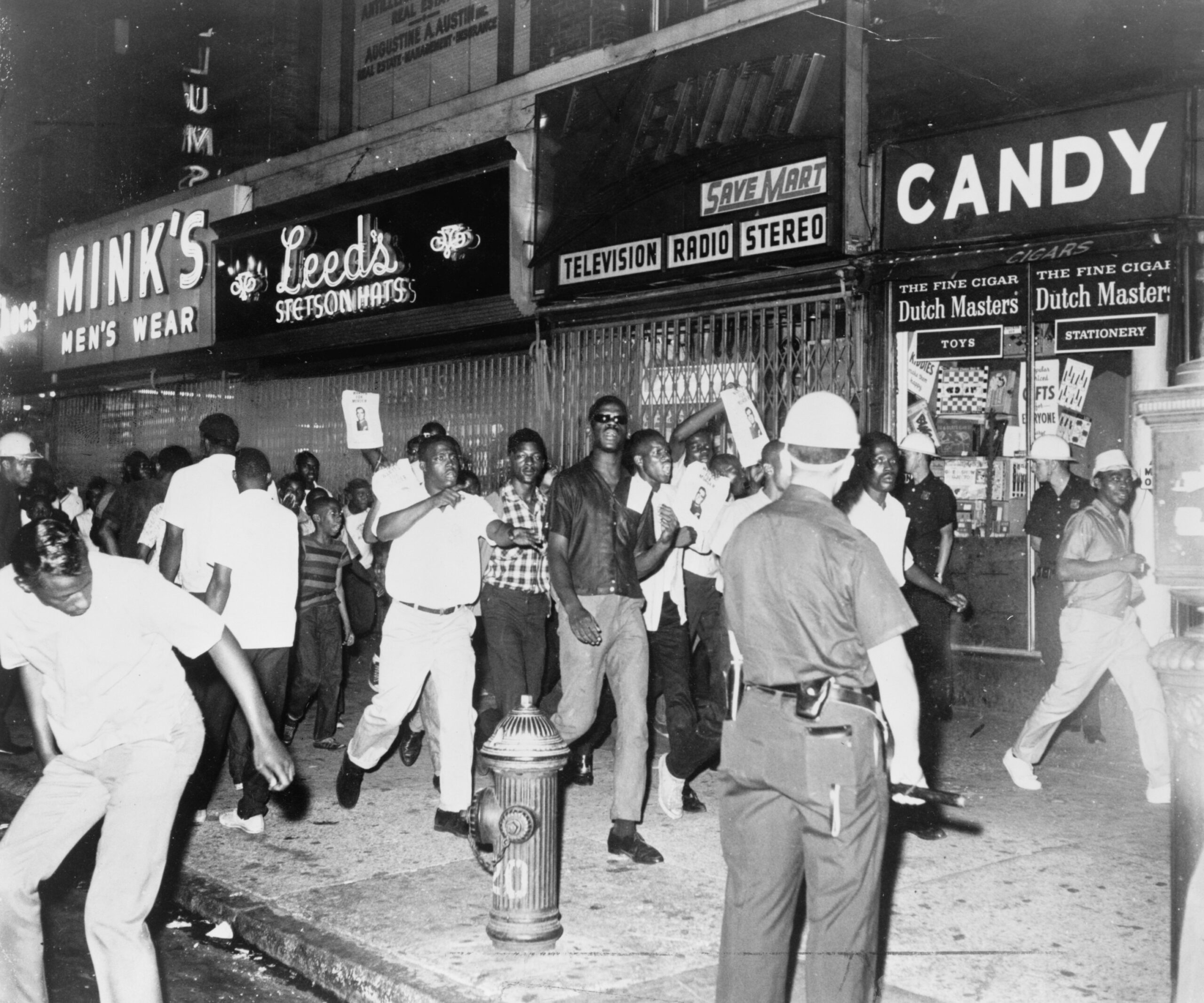

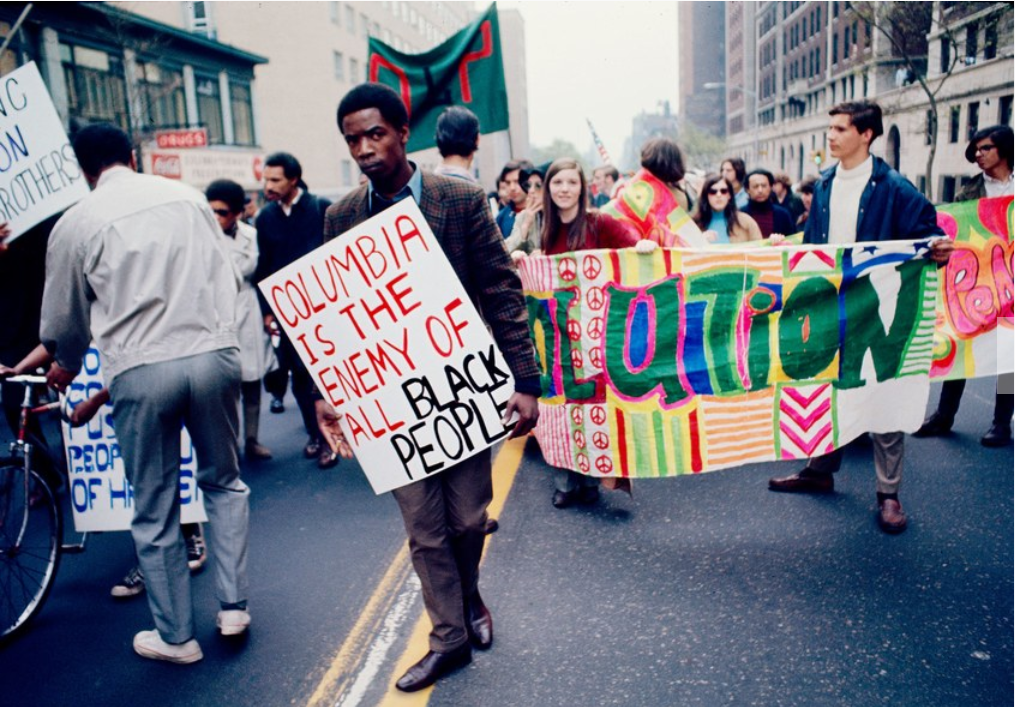

In July 1964, four years before Harlemites and Black Columbia students rose up in response to the University’s proposal to build a segregated athletic facility in Morningside Park, riots broke out in Harlem and various other parts of the city and country in response to the murder of a Black high school student in Harlem by an off-duty, White police officer.

These riots occurred only 21 years after another Harlem riot, in 1943, in response to a White police officer who shot an African-American soldier in Harlem and only 25 years before the Central Park Jogger case, which Adams cites as one of only two times that there were almost riots since he moved to Harlem in the 1980s.

Within the context of these spectacular events and other more everyday forms of racial bias and abuse experienced by people in Harlem, the importance of Lederer as a figure, Adams explains, is diluted. It was not Lederer who shot and killed James Powell in 1964, nor was it Lederer who shot and wounded Robert Bandy in 1943.

Dick De Marsico

With a consistent pattern of negative law enforcement interactions, the exact identity of a particular prosecutor or police officer, Adams tells me, loses its importance with time.

“For many people,” Adams says, “[Lederer is] just part of the nameless, faceless police, so Columbia students know who she is, but…” I interrupt Adams, and I tell him that for us she is also without a face, seemingly even without a uni, as her page on the Law School website shows.

Although Lederer may remain an anonymous figure for much of the neighborhood, the impact of the Central Park Five case is still a very real, lived experience for a lot of people in Harlem. At the time of the case, although the majority of mainstream media was ready to blame the five boys, a large community of people in Harlem doubted their guilt and pushed back against what they felt was a racially-biased trial.

“I don’t feel that I am very protected in an incident that I may be near or may be close to,” Belkis Valerio, a resident of The Bronx who works in Harlem, tells me in Spanish. “Because of discrimination or whatever it may be, I could become involved in a situation like that [like the Central Park Five].”

Many people of color in Harlem, like Valerio, believe that they could have taken the place of The Five and still can if they were to become involved in a similar situation today.

New York City Law Department

New York City Law Department

“It was because of their skin color,” says Donna Gooden, a Black Harlemite explaining her interpretation of the 1989 case. “It just breaks my heart because our Black kids, our Black boys are targets and victims.”

“Virtually most people in Harlem said ‘that could be my child,’” Adams says.

The community’s feelings about Lederer herself though are much murkier, even among The Five.

Santana, one of The Five, signed the petition against Lederer, but Wise, who served the longest sentence even though he wasn’t even in Central Park that night, feels more ambivalent about her.

“So what where she work at,” Wise says. “She’s doin’ her job.”

To some others in Harlem though, Lederer wasn’t doing her job at all.

“She wasn’t a good prosecutor,” says Miguel Clemente, a lifelong East Harlemite. “To me, my opinion, she wasn’t if she got these kids sentenced.”

Regardless of Lederer’s culpability for her work on the Central Park Jogger case, the fact is that, for many people in Harlem, Lederer is more than just a reflection of a racially-biased legal system. In continuing to hire Lederer, in staying silent about her role in the Central Park Five case, and in its lack of response to the 2013 petition, Columbia speaks to the Harlem community about its values.

As Derrick Moore, a Black Harlem resident who grew up across the street from the Central Park Five, explains “[Columbia] should take a more active role about who they hire and how it affects the people here in the community… Maybe, she is qualified to teach, or maybe not. I’m not sure about that, but it’s kind of disheartening that the process continues to be like ‘hell with the people that live here.’”

What residents like Moore feel is The University’s disregard for their community is exemplified by the fact that Columbia Law School has become a safe haven for Lederer in the middle of a neighborhood full of people who once actively despised her.

As the case went on, Lederer would commute to and from court surrounded by an outfit of police officers to protect her from the angry citizens outside, particularly people of color, who would yell insults and threaten her in outrage over the case and trial proceedings.

Chester Higgins, Jr.

Chester Higgins, Jr.

Even Wise, 16 years old at the time and the only one of The Five currently living in Harlem, turned to Lederer just after being charged for first-degree assault, sexual abuse, and riot and said “you bitch, you’ll pay for this. Jesus is going to get you.”

In 2013, Lederer received death threats as Burns’ documentary about the case as well as the petition to remove Lederer from Columbia renewed old anger against her.

Nowadays though, Lederer seems to be neither crowd-fearing nor God-fearing. When she finishes her class on Wednesday night at 8:10, she walks out of the front door of the Law School, crosses Amsterdam, and continues on through College Walk to Broadway alone.

While Lederer herself may feel secure on her way through campus, her presence at the school makes some students uneasy.

“I’m always gonna be wondering what that turning point would be for any of her Black students,” says Ayomide Omobo Law School ’21. “When do they stop being the good kid that she actually likes in her class and just be another Black child in the wrong place at the wrong time?”

Some other students though believe that having a controversial professor contributes to the intellectual diversity of the Law School.

“It’s another facet of education,” says one of Lederer’s current students. “It makes your legal education more real.”

Many students point out that Lederer’s story is only one out of many examples of systemic injustice at Columbia.

As Céline Zhu BC ’20, co-president of the Columbia Pre-Law Society, puts it “[at Columbia] we also have professors on this campus that do literal acts of violence that we turn a blind eye to… There’s so many other professors… that we allow to go through life and not really question either.”

Just this year, The Spectator discovered that the University has never taken tenure away from professors, even in instances where professors have been convicted of sexual harassment or assault.

In 2010, the same year that Lederer was hired, Gaviota Velasco SEAS ’11 reported being sexually harassed by a staff member in the Earth and Environmental Engineering Department and told The Spectator that “she never received a response from EOAA [the Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action] and had to continue working with her harasser”.

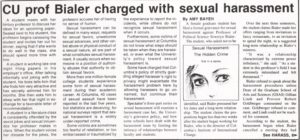

In November 1986, about two and a half years before the Central Park Five saga began, an anonymous student’s allegations of sexual harassment by then political science professor Seweryn Bialer were denied, and the University’s General Counsel pinned the problem as simply arising from Bialer’s “gregarious and open manner.” Bialer, who passed away this February, continued teaching at Columbia for another 11 years.

Columbia Daily Spectator/Nov. 19, 1986

Columbia Daily Spectator/Nov. 19, 1986

It is darkly ironic that these three incidences, which are only a portion of the published examples of faculty and staff misconduct against students, all involve ignored allegations of sexual harassment or assault. Lederer’s job is to prosecute exactly these kinds of crimes. Yet for those who view her as one in a number of implicit or explicitly violent faculty members at Columbia, Lederer is aligned with people like Velasco and Bialer. Like them, she is a faculty member with questionable morals and actions and whose presence causes some people to feel unsafe.

Even one of Lederer’s current students expresses their moral qualms about taking her class. They joined her class in spite of her history only because of what they say is the difficulty getting into any section of sample trial practice, much less guaranteeing that they are not in the one run by Lederer.

“Ethically, it’s conflicting” the student says. “It’s sort of hard to sit there and not consider her past… It’s in the back of my head the whole time, like especially when she says things about criminal defendants that seem somehow disrespectful.”

Omobo emphasizes that safety is not just physical but mental and emotional as well. Therefore, while Lederer, unlike Velasco or Bialer, does not commit any form of physical violence, she does cause some people, like Omobo, to feel emotionally violated.

Echoing Zhu’s comments though, Omobo says that, when she thinks more about it, she is actually not too shocked that Lederer works at Columbia.

“I’m surprised that this person did this thing, and then over the next couple of hours, I’m like ‘why am I surprised,’” Omobo reflects. “This is what it is. This is what it always is. This is what they always do. Columbia doesn’t care about us… This is just another way that they show it.”

Steve Schapiro

Steve Schapiro

Similar to Omobo, when I speak to Eric Seiff Law School ’58, who was Wise’s lawyer during the 2002 case, he tells me that the Law School’s continued hiring of Lederer is just “Columbia being Columbia.”

If Lederer is unexceptional, a mere manifestation of Columbia’s role as, what Omobo calls, “an instrument of White supremacy,” then maybe it makes sense that, in spite of a petition with thousands of signatures, an op-ed in The New York Times and a counter op-ed in The Atlantic by Ta-Nehisi Coates along with articles by BET, The New York Post, The Hollywood Reporter and others all about Lederer and her faculty position at our school, the majority of the people that I spoke to, including students at the Law School, had no idea who Lederer is or knew that she works at Columbia.

Before the publication of this article, Lederer’s name only appeared in The Spectator three times, each in relation to a rape case involving a Columbia student that Lederer worked on over four years prior to the Central Park Five case.

When I speak to the editor in chief and city news editor of The Spectator from 2013, the year that the petition encouraged coverage of Lederer in national news outlets, they both tell me that they don’t remember ever hearing about Lederer but that the story would have been one that The Spectator would have had an interest in covering.

The Spectator’s silence on this issue may be read as a testament to how insignificant Lederer’s story may seem against the backdrop of the many similar machinations of a University that, Zhu says, is “self-serving… [and] has an interest in maintaining itself” at the expense of some of its students and surrounding community.

Columbia Daily Spectator/Apr. 11, 2019

Columbia Daily Spectator/Apr. 11, 2019

The other importance of the absence of Lederer from the pages of our publication is that it reveals how The Spectator itself fits within a larger framework of media violence against the Central Park Five.

The response of The Spectator to Lederer is opposite that of many other media organizations, like the ones listed above. Instead, The Spectator, in choosing silence over speech, most resembles the responses of Lederer and of the University administration itself. However, the violence associated with Lederer’s silence, the University’s silence, and the silence of The Spectator is just one of many acts of violence mainstream media has wrought against The Central Park Five and people affected by the case.

The media plays an especially complicated role in the story of The Five. Sometimes through its silence and other times through its speech, media outlets have been accused of participating in the harm caused by the case and its aftermath.

In 1989 for example, the speed and voracity with which the media covered the Central Park Jogger story attributed an act and attitude of violence to “the wolf pack” even before they ever entered a courtroom.

By contrast, historian Craig Steven Wilder says in an interview for the The Central Park Five documentary that, in 2002, “I felt ashamed, actually, for New York, and I also felt extremely angry because their innocence never got the attention that their guilt did. The furor around prosecuting them still drowns out the good news of their innocence.”

New York Daily News/Apr. 21, 1989

New York Daily News/Apr. 21, 1989

During the original case, there were only a handful of newspapers that would publish Meili’s name, the victim of the crime. The constant speech expressed about the five young suspects was almost entirely absent for Meili, whose identity most mainstream media felt should be protected.

The Amsterdam News, a Black newspaper located in Harlem and one of the papers that decided to publish Meili’s name, made sure to break the silence about Meili in response to what they viewed as the unequal treatment afforded to Tawana Brawley, an alleged African-American rape victim who about a year earlier had had her image and name spoken all over national media.

Just as it was The Amsterdam News, the oldest Black newspaper in the country, who broke the silence about Meili, it is I, one of the few Black journalists at The Spectator, who break our 34-year silence about Lederer.

Following the publication of this article, there will be at least one more important speech act made about the Central Park Five. This summer, African-American director Ava DuVernay will release a Netflix miniseries, a narrative retelling of the Central Park Five story, called When They See Us.

Continuing to speak about the Central Park Five through media like this article or like DuVernay’s show is a crucial part of retaining an historical memory about an ever-repeating past, Adams tells me. Being an historian, it makes sense that Adams stresses how crucial history is to our understanding of the world and, by extension, to how we act in it.

It is a history of negative interactions with the police that affects how some Harlemites feel about the Central Park Five case. It is a history of allegedly violent faculty and staff members who maintain their employment at Columbia that affect how some students feel about the University. It is a history of loud media made about Lederer’s employment at the Law School that makes The Spectator’s silence so striking.

Dimitrios Kambouris

With an historical consciousness and knowledge, Adams sees how much of the past remains present in Harlem, especially regarding policing and violence against young Black men.

“Of course [people in Harlem are affected by the Central Park Five case today],” Adams tells me. “Because nothing’s changed… Amadou Diallo [a 23-year-old African-American man murdered in 1999 by four New York City Police Department officers, who were tried and acquitted] is no different than a Trayvon Martin or a Tamir Rice, so it just continues.”

And it continues not only in Harlem but also at Columbia.

On the night of Thursday, April 11th, nearly 30 years to the date of the Central Park Jogger crime, I, a 23-year-old African-American man, walked onto the campus of Barnard College, a school where many students are much like Meili: elite, young, White women. At the Milstein Center, I was confronted by a group of five to six Public Safety officers and was physically restrained and pinned against a countertop after non-violently refusing to show my Columbia ID.

The Barnard administration initially responded with silence, vaguely referring to an “unfortunate incident” in their original statement on the issue. Like Lederer, who declined our request to be interviewed for this article, the Barnard administration kept its mouth shut when asked to speak out against the racial bias of its Public Safety staff.

When Barnard finally changed its rhetoric, one Columbia student criticized what he called “cowardice at Columbia” as the administration gave in to pressure to acknowledge the racism involved in what had happened. When the charges against the Central Park Five were overturned, one of the case’s detectives, Michael Sheehan, similarly commented that “to vacate every one of these charges seems to me an act of moral cowardice and political correctness in the worst degree.”

When I reveal to Omobo who Lederer was in 1989 and who she is at our school today, she complains that “instead of hiring people who can make Columbia feel safe for everyone, you’re hiring someone who does the exact opposite”.

Columbia University Public Safety states that its mission is “to enhance the quality of life for the Columbia community… where the safety of all is balanced with the rights of the individual,” but not all of the individuals in the Columbia community see Public Safety officers as people who make them feel safe.

At the April 12th listening session about Barnard Public Safety’s treatment of me, one Black student says “We’ve all seen these highly publicized incidents of police brutality… [with] local police forces, but now it’s on campus police forces… Is the way that [a Black person] would interact with an outside police officer the same as how you would interact with a Public Safety police officer?”

Speaking to Omobo in the lobby of her residence hall just across the street from the Law School, she says “being Black in the US is always looking over your shoulder… [Knowing that Lederer works here] just means I’m gonna look over my shoulder just as much inside of Columbia Law School.”

Ian@NZFlickr

Ian@NZFlickr

In thinking about why the Central Park Five case received so much more media attention than other similar cases at the time, University of Connecticut sociology professor Gaye Tuchman theorizes that the location (Central Park), the timing (two years after the similar Tawana Brawley case), and the demographics (an upper-class White woman allegedly brutalized by lower-class Black men) made it the perfect story for mainstream media. The location (an Ivy League campus), timing (videos of police brutality have recently received a lot of press), and demographics (a Black man walking into a school of predominantly White women) of what happened to me was also a potent mix that made my story go viral.

The problem with these events though, Adams says, is that be it a Black man murdered by police, a Black student battered by campus safety officers, or Black boys wrongly incarcerated for a rape, the speech about the event eventually ceases to be spoken, and when it does, memories start to fade.

“Although people have been critical and say ‘oh! We must take this down. This is terrible,’ We forget,” Adams says. “We forget. Every bad thing, we forget it.”

• • •

On May 1st, 1989, 12 days after she was attacked, Meili awoke from her coma. In Burns’ documentary, some of The Five recall feeling relieved. Meili was so severely battered that it was unclear if she would survive, but when she woke, there was hope that her testimony would reveal the truth of what had really happened. When asked though, Meili couldn’t speak about the crime. She had forgotten. Reyes had beaten the memory right out of her brain.

Of all the absent statements in this story, Meili’s is the only one that was forced. Meili’s silence was an unwanted effect of her trauma, like the Central Park Five’s speech in 1989 was an effect of theirs.

Kaila Jones

Kaila Jones

Unlike Meili, people at Columbia and people in Harlem do remember the relevant past, and the University administration does too. Although time may make our speech about injustices gone by whittle down to whispers, there is no coma that keeps us from contextualizing Columbia’s actions. The question to consider then is how do we manage this memory. Do we say something, or do we, like Lederer, stay silent?

o