WeChat’s Race Problem

Blackface and Stereotyping in WeChat Stickers

news.mydrivers.com

news.mydrivers.com

NOVEMBER 13, 2017 | ![]() THE WORLD OF CHINESE

THE WORLD OF CHINESE

It wasn’t until I re-registered my account with a number beginning with +86 that I realized what WeChat has been hiding from those of us with foreign phones: blackface, Black question marks, and anti-Black racism in WeChat stickers.

Racism in Chinese media is by no means a great discovery. From the “This is Africa” exhibit at the Hubei Provincial Museum, where photographs of African people were put alongside photographs of wild animals, to the 2016 Qiaobi laundry detergent commercial, where a Black man is shoved into a washing machine and, once “cleaned,” comes out as Chinese, there is a persistent pattern of prejudice towards African and African diaspora peoples in China. Even WeChat, last month, was found guilty of this anti-Black bigotry when an African-American woman living in Shanghai discovered that WeChat’s translation software often turned the innocuous Chinese term for Black foreigner, “黑老外”, into “nigger,” a word whose roots in US slavery make it one of the most disrespectful referents for a Black person.

Dailymail

Dailymail

Neither is it surprising that there is un-wenming (uncivilized) media in WeChat’s sticker gallery. Although the third point in the WeChat Sticker Examination Standards Fundamental Requirements (微信表情审核标准基本要求) is “符合道德规则”, accords with moral regulations, there are, among the cats and bunnies and other cuddly creatures, images of beatings, suicides, and shit – like, literal shit – in the WeChat sticker gallery.

What makes these racist WeChat stickers worth examining is that, while they are invisible to users with US phone numbers, they borrow from and have at times even been birthed in an US aesthetic tradition. However, these stickers are also far from a simple case of Chinese Adadas, Sqny, or Sunbucks Coffee copycatting. Rather, the longevity and limits of these US media trends have not only been reproduced but also extended into a life of their own here in China.

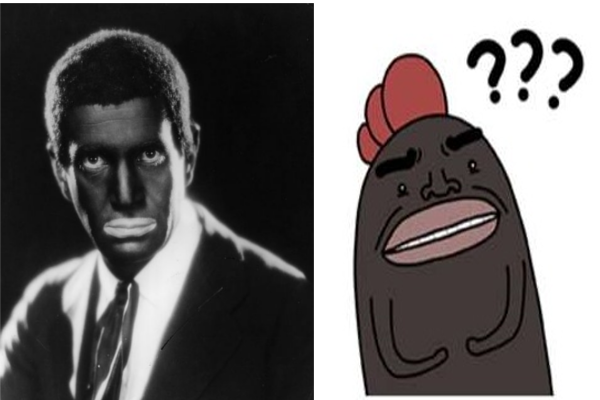

If you have a Chinese phone number and some knowledge of Chinese and for whatever reason a combined interest in WeChat stickers and Black people and as a result of all of these things happen to type the word “黑人,” Black person, into the search bar of your WeChat sticker gallery, 65 results will appear. Of these 65 results, about a quarter of them employ elements of a mid-19th century, US theatrical tradition called blackface.

Blackface originally referred to a practice of White actors putting dark make-up on to resemble Black people in a popular form of US entertainment called minstrel shows. The origin of the term minstrel describes a type of medieval, European entertainer, usually a singer whose voice would accompany a harp. Around 1830 though, the term came to refer to any show or groups of, usually White, performers imitating Black people. These imitations exaggerated racist stereotypes about Black people. Blackface was used as a way to emphasize the darkness of African-Americans’ skin and the largeness of their lips compared to White Americans.

Although it has largely been denounced in the US as a harmful and racist form of entertainment, remnants of US minstrelsy can still be seen in many aspects of US media today through certain Black stock characters, hip-hop music, clowns, and even Mickey Mouse. These representations desensitize White audiences to systematic oppression.

In China, WeChat stickers that borrow from blackface have achieved a similar end. According to Kaia Niambi Shivers, a New York University professor researching Black representation in media, they “relocate” blackface imagery and “normalize racism”.

Tumblr, WeChat

Tumblr, WeChat

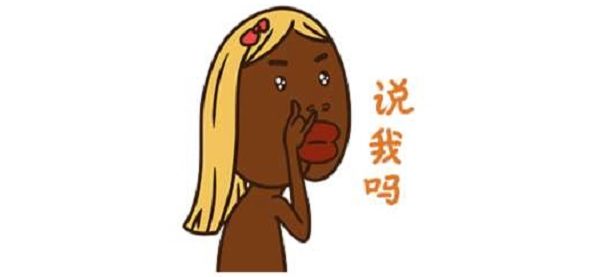

However, the creators and consumers of this media refute Shivers’ connection between blackface and biaoqingbao, sticker sets. WeChat does not allow users to contact sticker artists, and WeChat did not respond to any of TWOC’s inquiries regarding this story. Nevertheless, at least one WeChat artist, MisaChan whose only sticker gallery is a 16-sticker set called “Black Person Stickers” (黑人表情), writes in the gallery’s description ” [The character’s] name is 黑子 [the characters for “black” and “child”]. In Cantonese, 黑子 means bad luck. Also, the Black people stickers popular these days are pretty funny, so I drew some; there’s no racial discrimination.”

Similar language is used in a WeChat article about Black WeChat stickers called “This Race is Naturally Dramatic”. The author, BiuBiu在英国, appends to the end of their story a short P.S. about prejudice: “Note: this isn’t racial discrimination; this is racial worship.”

“Fat, African Slob” (WeChat)

“Fat, African Slob” (WeChat)

The closest things to a critical examination of these emojis are a 2016 article in The Beijinger about inappropriate WeChat stickers and a “comedic” WeChat article written in Chinese called “My White Friend Says: ‘Black People Question Question Question’ Stickers Are Racial Discrimination,” which reinterprets the author’s White friend’s reaction to Black stickers as outrage that there aren’t enough White people stickers.

“Are you talking about me” (WeChat)

“Are you talking about me” (WeChat)

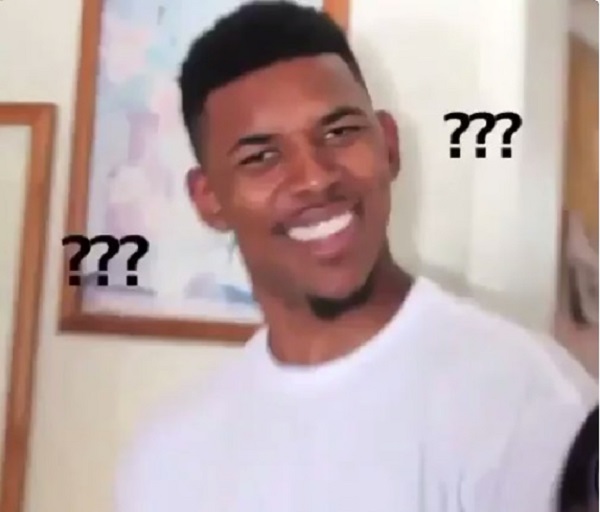

Both the satire piece and the article by BiuBiu在英国, though, refer to stickers with more recent aesthetic referent than 19th-century theater: a 2016 meme from the US called “Confused Nick Young.” As countless WeChat articles explain, the original meme was a screenshot from a short YouTube video about NBA player Nick Young, called “Day in the Life of Nick Young.” In the video, Young, who is African-American, gives his mother a confused, questioning look when she comments that he was a “clown” when he was younger. Though the image was widely shared and parodied in the US—including within Black communities—the meme has never achieved the virality there that it did in China.

YouTube

Just as, in the US, the word used to describe a European singer in medieval times became imbibed with connotations of racism and White supremacy, in China, the “Confused Nick Young” image became known as 黑人问号, “Black person question mark”. Of the 65 results for 黑人 in WeChat’s official sticker gallery, over 80 percent have stickers called 黑人问号. As WeChat user KFM981 describes in a WeChat article, “all one needs is black skin + a slow expression + an off-line lighting engineer, and it’s hard to evade the fate of ‘becoming a sticker.’”

In reality, it’s even simpler than that. 黑人问号 has become so embedded as an expression of confusion in Chinese internet language that many of the stickers do not even resemble Black people. The term has been removed from its original meaning and become simply a replacement for the word “confused.”

Non-Black and non-blackface stickers identified on WeChat as 黑人问号. (WeChat)

Non-Black and non-blackface stickers identified on WeChat as 黑人问号. (WeChat)

For example, in a WeChat article unrelated to race, there’s the sentence: “Right when the assistant saw the news, he also had a ‘Black person question mark’ expression.” In another article about cell phones, the author writes, “When faced with Chinese-made Gaorui mobile phone’s 3,000 yuan selling price, consumers used to paying 2,499 yuan, 1,999 yuan, or even 999 yuan for a flagship model should all have a ‘Black person question mark’ expression.”

Shivers points out that, although the applications of this expression have moved beyond a racial context, “Black person question mark”, no matter where or how it is used, will always be connected back to Black people as a kind of cultural geography; the confused gesture has been internalized as a Black act.

Furthermore, Shivers mentions that the idea of a questioning Black person is also rooted in the minstrel tradition. Minstrelsy had its own set of stock characters from Uncle Tom and Zip Coon to Buck, Pickaninny, Jezebel, Mammy, and Jim Crow. “Black person question mark” relates to the Tambo and Bones minstrel characters, whom audiences appreciated for their simple-mindedness.

A drawing of a pickaninny beside a 黑人问号 WeChat sticker. (historyonthenet.com, WeChat)

A drawing of a pickaninny beside a 黑人问号 WeChat sticker. (historyonthenet.com, WeChat)

The comparison between lighthearted WeChat stickers and racist antebellum entertainment may sound extreme; it may seem unreasonable that a sticker could subjugate a race of people, but in some sense, that is exactly what is happening. The “Black person question mark” has, for some WeChat users, become an identifier of Blackness just as characteristic as dark skin. As KFM981 writes, “Nowadays, if you just come across a Black friend, you will automatically add a question mark to their forehead.”

Seeing Black people with question marks floating around their foreheads “removes dignity and integrity and actually humanity from people,” Shivers says. “People of African descent are caricatures in the eyes of people who do not understand the culture of the people…This is an extension of this idea about Black people not being human.”

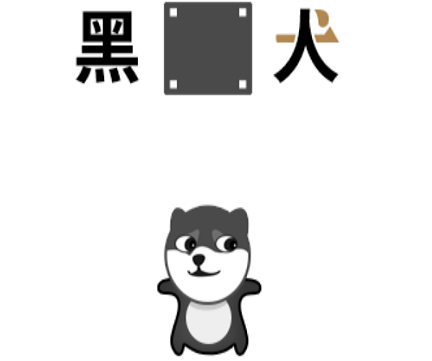

A visual play on words that both says Black person “黑人” and black dog “黑犬.” (WeChat)

A visual play on words that both says Black person “黑人” and black dog “黑犬.” (WeChat)

Nick Young, for example, is hardly ever described simply as Nick Young in WeChat articles. He is called “黑人问号 boy” or something along the same lines. Even when Young’s name is used, it is only written after the phrase “Black person question mark,” as in the headline for the WeChat article “Iggy Azalea and NBA Black Person Question Mark Face Nick Young Break Up!”

Writing about her trip to Ghana with volunteer organization AIESEC, a student from the Communication University of China admits through her chapter’s WeChat account that Black people “usually emerge in my stickers and funny jokes. Therefore, after I arrived [in Ghana] I finally realized the old me had a lot of areas of misunderstanding.”

____Despite attesting to the humanity of Black folk, the article is titled “Me and ‘Black Person Stickers’ First Meeting”. This suggests that this student still perceives what she learned about Blackness in Ghana through the culturally-embedded expectations developed from stickers on her phone.

“African Chief” (WeChat)

“African Chief” (WeChat)

Emoji racism has lately become recognized in the US. In 2016, in response to complaints that its humanoid emoji options were limited to characteristically Caucasian or cartoonish bright yellow faces, Unicode Consortium, a non-profit organization that makes emojis for Apple, Android, Windows, and other companies, released a new set of racially-inclusive emojis, which allow users to adjust the color of the emoji they send to a shade that is suitable for them. Other emoji-making companies such as EverythingAmped Inc., based out of San Francisco, and AfMob, in Cape Town, have also released their own versions of inclusive emojis such as “Black Emoticons,” “AfroMoji,” and “MusliMoji.”

The reactions to these efforts have been varied. At the time of the Unicode emoji release in 2016, it was argued that these emojis were creating an even more discriminatory social media environment. The debate has been reported in Chinese-language WeChat articles, but the introspection hasn’t extended to the ways that racism manifests in emojis in the Chinese context.

The sticker on the left reads “Africa”, on the right “Europe.” These are the only continents represented in this sticker gallery. (WeChat)

The sticker on the left reads “Africa”, on the right “Europe.” These are the only continents represented in this sticker gallery. (WeChat)

“[These stickers] normalize White supremacy,” Shivers says. Chinese people who create or disseminate these stickers, who themselves are not White, “are actually playing into the very system that racializes and oppresses them.

“Because they come from a White supremacist history, [these stickers] create and continue this idea that a non-White person will never have the power, will never have the genes, will never have the language, will never have the culture that is equal to European, Anglo culture, and will forever be the White man’s slave.”